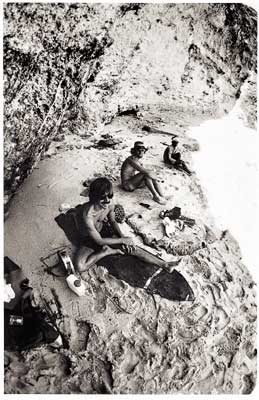

Bernie Baker, El Zunzal, El Salvador, circa 1970. Photo: Monty Smith.

One of the most incredible chapters in the annals of global exploration, as within the past 100 years, members of a small, disparate subculture pressed out against the borders of the known world, until today they've left their barefoot tracks on virtually every coastline on this Ocean Earth. Braving hardship, loneliness, disease and perils unnumbered; without maps or provenance, driven on only by a collective vision of...fun. Racing to face the storm, to pit themselves against one of the most powerful forces in the universe, the same awesome energy that has leveled great cities, drowned mighty armadas and wiped empires clean from the face of the earth, not running from but searching for this interface, this violent frontier, and all for...fun. Spread out across this planet, their lines of migration wrapping the globe in a fine lace, stringing pole to pole, continent to continent, hemisphere to hemisphere; from Kauai to the Kurils, from the Andamans to Antarctica, from Northern California to South Australia, from Spitzbergen to Sumatra, from Japan to Java, from the West Indies to West Timor and back again. A romantic, relentless tale of discovery unique in all of history, this epic quest for sport, for enlightenment. For fun. The story of surf exploration.

Jurassic PeakIt begins, of course, with the Polynesians. As early as 2000 B.C., the ancestors of the Polynesians began their eastward migration from Southeast Asia, in most cases riding wind and swell in their innovative, twin-hulled voyaging canoes as they populated the vast Pacific. In this sense, an entire culture "surfed" its way into existence. At every stop along the way, recreational wave riding popped up in some varied form or another. But it wasn't until the first canoes reached Hawaii in 400 A.D. that the story of surf exploration begins. In the centuries between its initial settlement and the first contact with European explorers in the 18th century, Hawaiian board surfing had developed to an amazing degree. As explained by University of Hawaii anthropologist Ben Finney in his seminal 1966 work, Surfing, a History of the Ancient Hawaiian Sport:

Modern

baggage, timeless posture. Photo: Divine.

"First, those early canoe voyagers,

who initiated the exploration and colonization of the Pacific some 4,000

years ago, developed rudimentary board surfing: primarily a children's

pastime practiced with short bodyboards. As their descendants pushed farther

into the Pacific, they carried this pastime with them. Then, on some of

the main islands of East Polynesia, it came to be taken up more and more

by adult men and women using larger boards. Finally, along the shores

of the Hawaiian Islands, surfing reached its peak. There the feat of standing

erect on a speeding board found its finest expression."

"First, those early canoe voyagers,

who initiated the exploration and colonization of the Pacific some 4,000

years ago, developed rudimentary board surfing: primarily a children's

pastime practiced with short bodyboards. As their descendants pushed farther

into the Pacific, they carried this pastime with them. Then, on some of

the main islands of East Polynesia, it came to be taken up more and more

by adult men and women using larger boards. Finally, along the shores

of the Hawaiian Islands, surfing reached its peak. There the feat of standing

erect on a speeding board found its finest expression."

The degree to which surfing was integrated into ancient Hawaiian society makes today's paltry surf culture pale in comparison. Much has been written about this, from the logs of early 19th century missionaries like William Ellis ("the thatch houses of a whole village stood empty, daily tasks such as farming, fishing and tapa-making were left undone while an entire community--men, women and children--enjoyed themselves in the rising surf....") to the more modern paeans to Hawaiiana that appear in various surf periodicals' annual North Shore issues. But Hawaii's real gift to the world wasn't so much the sport itself but rather a vital and potent institution within the sport: the search for surf.

Modern stand-up board surfing was developed at relatively accessible breaks like Kealakekua Bay on the Kona coast of the Big Island of Hawaii. King Kamehameha even surfed there. Yet unlike most stereotypical images of ancient Hawaiian surfing, all the action didn't take place out in front of the village. By the mid-1800s, intrepid Island surfers ranged throughout the Hawaiian chain, exploring for surf not only near the major population centers but also on rugged, lonely coastlines, testing their daring and skill at famous breaks like Molokai's Ka-laupapa, Ni'ihau's Ka'unu-nui and Maka-iwa, "mother of pearl eyes," on far-off Kauai. This pattern of discovery is singular among indigenous people in that it was for the most part motivated by nothing more than the pursuit of recreational sport. These early explorers weren't looking for new grazing or farming land, rich fishing grounds or access to fresh water. They weren't hunting for food or land or women. These were surfers, with a wanderlust born of the desire to discover new challenges, new ocean vistas, new waves to surf. Our Polynesian predecessors set a pattern that had a much wider ranging influence on surfing culture to come than did the more traditional image of the happy Hawaiian beachboy. The irony is that when the surfing virus jumped hosts at the turn of the 20th century, it did so not in keeping with a legacy of adventure and discovery but rather in its most influential cases for purely commercial reasons. Consider that when in 1907, 23-year-old George Freeth first board-surfed the waves off Redondo Beach, to set rolling the whole ball of wax, so to speak, he did so as a paid professional, sponsored by the Pacific Electric Railway to promote its LA-South Bay line.

Even more of an accidental pioneer was the great Duke Kahanamoku, today considered the father of modern surfing. The Duke, a major source of inspiration to early Californian surfers and credited with introducing the world to the sport, did so quite whimsically. In both celebrated instances--when in 1910 the Duke first surfed Ocean City, N. J., and later brought stand-up board surfing to Australia at Sydney's Freshwater Beach in 1915--he did so as a swim star, performing promo junkets for the U.S. Olympic swimming team and the Red Cross lifesaving corp. Hemmed in by itineraries and schedules, perhaps a little uneasy with his role as a "prize racehorse," it was only natural that Duke head down to the beach and take a look at the surf and then obviously want to paddle out. But it was hardly the reason he was there. The waves were not why he went.

Acknowledging this, it's easy to see that the ensuing waves of Californians who in the front half of the 1900s voyaged back to Hawaii in deliberate search of surf were responding to a precedent set by surfers centuries old. It is a precedent we follow today, the proliferation of surfing throughout the globe owing more to the ancient Hawaiians than any modern tourist bureau's vision of life on the beach at Waikiki. It also explains our enduring affinity for floral prints.

Beyond Diamond Head

From these early flashpoints, the flame ignited. By the 1940s, Hawaii was still the epicenter of the surfing world, but in a clear case of reverse-colonization, seeds had blown across the sea with the trades and taken purchase on foreign shores. Carlos Dogny, a visitor to Hawaii in 1937, brought a surfboard home with him to his native Peru, and an entire surf culture sprung up in that image, complete with the opulent Club Waikiki, on the beach of Miraflores, just outside Lima. In Australia, post-Kahanamoku surfing still remained within the domain of the surf lifesaving clubs, restricted mostly to the beaches of Sydney, performed on long, hollow paddleboards that were, in fact, nothing like the relatively nimble 10-foot piece of pine the Duke surfed on. Traveling lifeguards had, in the late-1930s, introduced the sport to the beaches of Durban in South Africa long before the advent of shark nets, which might explain its limited growth. In 1939, two sons of affluent coffee-growers from Santos, Sao Paulo, read Tom Blake's widely influential hollow surfboard construction article in Popular Mechanics, fashioning Brazil's first surfboards from local wood. But in all these flowering scenes, the mood was one of inspired mimicry more than actual mission. The real movement was born in California. Pre-WWII West Coast surfers had almost unwittingly taken the best of Waikiki then flavored it with a dash of counterculture and a touch of the vagabond. Unlike the beachboys they felt they were emulating so accurately, California surfers were actually a wandering breed, traveling up and down the coast from Santa Monica to La Jolla--with a far-flung outpost in frigid Santa Cruz--in search of new surf. The perfect, peeling waves of Malibu were discovered in this way, when in 1927 Tom Blake and Sam Reid took a drive up the then-wild Coast Highway and came upon a wave that challenged their very imagination; the obvious symmetry of the point break forcing them to re-evaluate the act itself.

Wayne

Striegel and the peripatetic Peter Troy (with board bag),

on an early Canary Islands foray. Photo: Sands.

Then in 1932, Lorrin "Whitey"

Harrison and Preston "Pete" Peterson took one of the first concerted

surfaris, cross-pollinating back across the broad Pacific to Hawaii. Sailing

again, this time with Harrison stowing away aboard an ocean liner, where

he was subsequently nabbed and forced to work his passage. But he got

back to surfing's homeland, and both he and Peterson lived right on the

beach at Waikiki, riding every break they could paddle to, from Diamond

Head to Kekai-o-Mamala, at the mouth of what today is the Honolulu harbor.

They eventually stowed away back to the Mainland on the U.S.S. troop ship

Republic, disguised as soldiers, and with their tales of pristine surf

and warm offshore winds to inspire generations of surfers to come. At

the same time, a group of Hawaiian surfers took up the search again, with

pioneers like Wally Froiseth and George Downing re-discovering the big-wave-potential

of breaks like Makaha and Sunset Beach on Oahu's North Shore. In 1947,

Froiseth, Downing and fellow Islander Russ Takaki even manned a schooner,

sailing it to California, where they toured the coast with their narrow-tailed

"Hot Curls." But these were all small steps, and surfing dreams

had yet to take on a global scale.

Then in 1932, Lorrin "Whitey"

Harrison and Preston "Pete" Peterson took one of the first concerted

surfaris, cross-pollinating back across the broad Pacific to Hawaii. Sailing

again, this time with Harrison stowing away aboard an ocean liner, where

he was subsequently nabbed and forced to work his passage. But he got

back to surfing's homeland, and both he and Peterson lived right on the

beach at Waikiki, riding every break they could paddle to, from Diamond

Head to Kekai-o-Mamala, at the mouth of what today is the Honolulu harbor.

They eventually stowed away back to the Mainland on the U.S.S. troop ship

Republic, disguised as soldiers, and with their tales of pristine surf

and warm offshore winds to inspire generations of surfers to come. At

the same time, a group of Hawaiian surfers took up the search again, with

pioneers like Wally Froiseth and George Downing re-discovering the big-wave-potential

of breaks like Makaha and Sunset Beach on Oahu's North Shore. In 1947,

Froiseth, Downing and fellow Islander Russ Takaki even manned a schooner,

sailing it to California, where they toured the coast with their narrow-tailed

"Hot Curls." But these were all small steps, and surfing dreams

had yet to take on a global scale.

A World of Waves

New

School travel veteran Chris Malloy, faced with awesome

symmetry in Mindanao, Philippines. Photo: Callahan.

Imagine living in Manly Beach, Australia,

in 1956. All the Queenscliff boys have been talking about is the American

lifeguard team's visit: Greg Noll, Mike Bright, Tom Zahn and Bob Burnside.

Oh, the Okkers kicked their bums in the paddle races and lifeguard events.

But how the Yanks could surf on their lightweight balsa Malibu boards,

turning in and out of the curl, riding high on the face, racing across

the wall instead of straight in toward shore. Australian surfing changed

in an instant. A skinny grom named Bob Evans bought Noll's board, and

suddenly there was a balsawood shortage all across central New South Wales.

But the Malibu boards did more than innovate technique. Suddenly free

from their clumsy, hollow kook boxes, Aussie surfers like Evans, Bluey

Mayes, Nipper Williams and Owen Pillon began looking away from the beaches

of Sydney, and the first tentative surf trips began along the coast of

that great island continent. From this beginning would stem one of the

most fertile branches of surfing's worldwide dispersal, pushing up three

sides of Terra Australis, and eventually out into the South Pacific and

then north into the Indian Ocean and the fabulously wave-rich Indonesian

Archipelago. But these discoveries were still decades off. Meanwhile in

California, restless surfers turned their sights in an obvious direction:

south across the border into Mexico. Once again, Greg Noll from Manhattan

Beach was one of the prime movers, launching some of the first expeditions

to Mainland Mexico: Acapulco and Mazatlan in the late 1950s. This was

some of the sport's first true exploration, as adventure still lay alongside

the paved road in most locations. Keep in mind there was not much road

of any kind leading into Baja California. These early pushes differ from,

say, when George Downing brought the first balsa board to Peru in 1955,

or Bud Browne's visit to Australian shores while filming Australian Surfriders

in 1959, in that they were actual forays into the unknown. In the years

that followed, Mexico's coast would slowly reveal its treasures: 3Ms and

San Miguel in Northern Baja, San Blas's Matanchen Bay--the "longest

rideable wave in the world"--and later, the beachbreaks of Petacalco

and Puerto Escondido.

Imagine living in Manly Beach, Australia,

in 1956. All the Queenscliff boys have been talking about is the American

lifeguard team's visit: Greg Noll, Mike Bright, Tom Zahn and Bob Burnside.

Oh, the Okkers kicked their bums in the paddle races and lifeguard events.

But how the Yanks could surf on their lightweight balsa Malibu boards,

turning in and out of the curl, riding high on the face, racing across

the wall instead of straight in toward shore. Australian surfing changed

in an instant. A skinny grom named Bob Evans bought Noll's board, and

suddenly there was a balsawood shortage all across central New South Wales.

But the Malibu boards did more than innovate technique. Suddenly free

from their clumsy, hollow kook boxes, Aussie surfers like Evans, Bluey

Mayes, Nipper Williams and Owen Pillon began looking away from the beaches

of Sydney, and the first tentative surf trips began along the coast of

that great island continent. From this beginning would stem one of the

most fertile branches of surfing's worldwide dispersal, pushing up three

sides of Terra Australis, and eventually out into the South Pacific and

then north into the Indian Ocean and the fabulously wave-rich Indonesian

Archipelago. But these discoveries were still decades off. Meanwhile in

California, restless surfers turned their sights in an obvious direction:

south across the border into Mexico. Once again, Greg Noll from Manhattan

Beach was one of the prime movers, launching some of the first expeditions

to Mainland Mexico: Acapulco and Mazatlan in the late 1950s. This was

some of the sport's first true exploration, as adventure still lay alongside

the paved road in most locations. Keep in mind there was not much road

of any kind leading into Baja California. These early pushes differ from,

say, when George Downing brought the first balsa board to Peru in 1955,

or Bud Browne's visit to Australian shores while filming Australian Surfriders

in 1959, in that they were actual forays into the unknown. In the years

that followed, Mexico's coast would slowly reveal its treasures: 3Ms and

San Miguel in Northern Baja, San Blas's Matanchen Bay--the "longest

rideable wave in the world"--and later, the beachbreaks of Petacalco

and Puerto Escondido.

Tavarua

in Fiji--the Gold Standard of 21st-century surf travel.

Photo: Jeff Divine.

The early 1960s were the Golden Age

of surf travel. With the advent of lighter, more manageable polyurethane

foam boards, and the first era of affordable air travel, the world seemed

wide open. All you had to do was go look--and sometimes not even do that.

France's Joel de Rosnay, visiting his father's sugar plantation on Mauritius

in 1963, literally stumbled onto the flawless lefts of Tamarin Bay ("It's

a left slide," he reported, "with the most wonderfully shaped

waves you can imagine.") Competitors invited to Peru's lavish annual

international championships--John Severson, George Downing, Australians

Peter Troy and Bob Pike among them--pushed out from Club Waikiki, discovering

new breaks like Cerro Azul and Kon Tiki. California surfer/yachtsmen--including

soon-to-be-legend Phil Edwards--cruising home from winter climes in Mexico,

left tracks on isolated islands like the Soccoros, breaks that have hardly

seen a surfer since. And scores of U.S. servicemen, scattered like lone

missionaries, nursing their faith so far from home on the shores of Japan,

Guam in the Pacific and Puerto Rico in the Caribbean; virgin blue curls

at "Tracking Station" near the U.S. Air Force base in St. Croix.

The early 1960s were the Golden Age

of surf travel. With the advent of lighter, more manageable polyurethane

foam boards, and the first era of affordable air travel, the world seemed

wide open. All you had to do was go look--and sometimes not even do that.

France's Joel de Rosnay, visiting his father's sugar plantation on Mauritius

in 1963, literally stumbled onto the flawless lefts of Tamarin Bay ("It's

a left slide," he reported, "with the most wonderfully shaped

waves you can imagine.") Competitors invited to Peru's lavish annual

international championships--John Severson, George Downing, Australians

Peter Troy and Bob Pike among them--pushed out from Club Waikiki, discovering

new breaks like Cerro Azul and Kon Tiki. California surfer/yachtsmen--including

soon-to-be-legend Phil Edwards--cruising home from winter climes in Mexico,

left tracks on isolated islands like the Soccoros, breaks that have hardly

seen a surfer since. And scores of U.S. servicemen, scattered like lone

missionaries, nursing their faith so far from home on the shores of Japan,

Guam in the Pacific and Puerto Rico in the Caribbean; virgin blue curls

at "Tracking Station" near the U.S. Air Force base in St. Croix.

Puerto

Vallarta by air: a new look at an old spot. Mike Losness.

Photo: Randy Dible.

And here were the restless souls,

harkening back to the great Victorian age of exploration in the late 19th

century, when chartered vagabonds like Captain Richard Burton wandered

into the blank spaces of the African map, searching for the source of

the Nile in the Mountains of the Moon. Australian photographer Ron Perrott

from Dee Why both exemplified and chronicled this new ethic. In the same

way that pioneers like Tom Blake and Doc Ball provided vital Hawaii/California

imagery in the 1930s and '40s, Perrott chronicled the passionate, innocent

hunger for new wavescapes that characterized the early 1960s. His classic

shot of Angourie, on New South Wales' North Coast, opened up a whole side

of a continent. But then Perrott just kept on going: South Africa, Seychelles,

Europe. Breaking trail, sending dispatches, calling back for others to

follow.

And here were the restless souls,

harkening back to the great Victorian age of exploration in the late 19th

century, when chartered vagabonds like Captain Richard Burton wandered

into the blank spaces of the African map, searching for the source of

the Nile in the Mountains of the Moon. Australian photographer Ron Perrott

from Dee Why both exemplified and chronicled this new ethic. In the same

way that pioneers like Tom Blake and Doc Ball provided vital Hawaii/California

imagery in the 1930s and '40s, Perrott chronicled the passionate, innocent

hunger for new wavescapes that characterized the early 1960s. His classic

shot of Angourie, on New South Wales' North Coast, opened up a whole side

of a continent. But then Perrott just kept on going: South Africa, Seychelles,

Europe. Breaking trail, sending dispatches, calling back for others to

follow.

In

the 1960s, there wasn't much paved road in Baja--but that

didn't stop adventurous surfers. Photo: Ron Stoner.

Then there was Australia's Peter Troy,

perhaps the greatest surf adventurer ever. Troy, a Torquay surfer who

in the early 1960s popularized surfing at Bells Beach, even grading the

first road to the break with a "borrowed" Shire bulldozer, first

took to the road in 1963. During his epic three-year surfari, Troy visited

Ceylon, Italy, England, France, Portugal, Spain, the Canary Islands, Puerto

Rico, Florida, California, Hawaii, Mexico, Peru, Ecuador, Argentina, Brazil,

Panama and El Salvador. In the process, he brought the first foam board

to Brazil, introduced surfing to the Channel Islands and Argentina, and

was the first to ride Punta Rocas in Peru; a full decade later, the peripatetic

Aussie would help discover the dreamy right at Lagundi Bay, Nias, while

riding a motorcycle across Indonesia.

Then there was Australia's Peter Troy,

perhaps the greatest surf adventurer ever. Troy, a Torquay surfer who

in the early 1960s popularized surfing at Bells Beach, even grading the

first road to the break with a "borrowed" Shire bulldozer, first

took to the road in 1963. During his epic three-year surfari, Troy visited

Ceylon, Italy, England, France, Portugal, Spain, the Canary Islands, Puerto

Rico, Florida, California, Hawaii, Mexico, Peru, Ecuador, Argentina, Brazil,

Panama and El Salvador. In the process, he brought the first foam board

to Brazil, introduced surfing to the Channel Islands and Argentina, and

was the first to ride Punta Rocas in Peru; a full decade later, the peripatetic

Aussie would help discover the dreamy right at Lagundi Bay, Nias, while

riding a motorcycle across Indonesia.

If surf adventure has a soul, it is Peter Troy's.

The remainder of the '60s was a magic time, the whole globe a watery Sinbad's cave full of glittering riches, an age of lost mines and treasure maps. In 1965, surf writer Bill Cleary heard the tale of how Santa Monica novelist and screenwriter Peter Viertel, working in France on a 1956 movie version of The Sun Also Rises, had his Quigg balsa shipped over, introducing surfing to the Cote du Basque and south into Spain. Viertel was also reputed to have first surfed the waves of Puerto Vallarta, Mexico, visiting with his wife, actress Deborah Kerr, while she filmed Night of the Iguana. There, it was rumored, Viertel had discovered a "Mexican Malibu."

Sprung

up in the image of visiting surfers, indigenous surf cultures

have, over the decades, taken on their own colorful style. Angel

Salinas, Puerto Escondido. Photo: Ruben Pi–a.

Cleary went on the chase in a scene

straight out of an Indiana Jones movie. He sought out Viertel, arranging

a meeting in a bungalow at the Hotel Bel-Air in Beverly Hills. "I

wanted to turn the conversation to Mexico, to the hidden Malibu--but how?"

Cleary wrote in his 1965 SURFER feature. "I grew nervous and was

just about to blurt out my question when Viertel, perhaps intuitively,

began speaking of Mexico and Puerto Vallarta. As I listened, he described

a series of beautiful coves, points and reefs; lobsters crawling from

the sea; warm, clear water and pink-sand beaches. He had seen a world

of surf and told no tales. I could barely contain my excitement.

Cleary went on the chase in a scene

straight out of an Indiana Jones movie. He sought out Viertel, arranging

a meeting in a bungalow at the Hotel Bel-Air in Beverly Hills. "I

wanted to turn the conversation to Mexico, to the hidden Malibu--but how?"

Cleary wrote in his 1965 SURFER feature. "I grew nervous and was

just about to blurt out my question when Viertel, perhaps intuitively,

began speaking of Mexico and Puerto Vallarta. As I listened, he described

a series of beautiful coves, points and reefs; lobsters crawling from

the sea; warm, clear water and pink-sand beaches. He had seen a world

of surf and told no tales. I could barely contain my excitement.

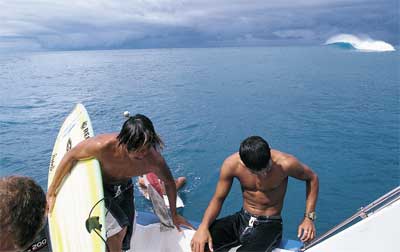

The camp at G-Land--no

longer as chic as a Mentawai boat trip, (above)

but just as challenging as ever. Photos: Findo and Divine.

'How does one get there?'

'How does one get there?'

'By jeep,' Viertel said. 'It's about three hours through the jungle. But jeeps are expensive. I think it's easier by boat.' 'But it's hard to recognize surfing spots from the water. Are there any landmarks? Is there a village nearby?'

'Here,' he said, sitting down at a desk. 'I'll draw you a map....'"

It was a glorious period--a wonderful time to be a surfer with a valid passport and a sore arm. But this sense of wonder couldn't last, and the days of drawing maps would soon be over.

The Myth of Perfection

The ethos that came to define surf travel in the 1970s was actually born in the early '60s--1963, to be exact. We all know the tune: the gentle guitar stains of the theme to The Endless Summer conjuring up images of exotic surf to this day.

Bruce Brown's landmark film, synthesizing so perfectly the essence of surf travel--the Ghanaian village scenes, funky surf in Tahiti, the endless walls of Raglan in New Zealand--also introduced a powerful new ethic that would come to eclipse all the travelogue. This was the idea--the very conception--of a "perfect" wave. In The Endless Summer's concise, supremely eloquent Cape St. Francis sequence, an ulterior motivating force took root, a new ethic that within seven years would completely reshape surfing's map. Whereas before the thing was simply to go, now there was a definitive goal, an El Dorado. By 1970, surfers weren't just looking, but looking for something better: a quest for perfection.

Longtime

Indo hands Gerry Lopez and Bert Barkson,

Uluwatu cave, 1977. Gerry put the most recognizable

face on Indonesian surf adventure in the 1970s.

Photo: Dick Hoole.

Consider the great Indonesian wave

rush. Touristing French and Australian surfers had been riding the beach

breaks of Kuta, on Bali, since the early 1970s; a young Bertie Barkson

and his mates rode the peeling lefts of Kuta Reef off the end of the airport

runway. But then in 1971, while on Bali filming The Morning of the Earth,

Australian filmmaker Alby Falzon took surfers Rusty Miller and Stephen

Cooney on a day trip out to the temple at Uluwatu, on the southwestern

tip of the island. Falzon's tale is one of the greats: seeing the lines

of swell sweep the cliffs, tramping through the countryside, looking for

a way down to the water, the heat, the curious villagers, the ravine,

the cave, and through the cave a path to the reef and one of the best

waves the surfing world had ever seen. Uluwatu's discovery rocked the

surf world. Gerry Lopez, the most famous surfer at the time, flew over

and set to colonizing the Bukit peninsula one glassy barrel at a time.

But Indo-Inflation was already setting in. American surfers Bob Laverty,

Bill Boyum and Bert Barkson, in an attempt to one-up the Ulu converts, blazed

a trail through the untracked jungles of nearby Java and a wave they'd

spied from an airliner in a region called Grajagan. Within a year, G-Land

was the spot: better, longer, faster--more perfect--than Uluwatu and a

lot less crowded. This insatiable drive would, within the decade, bring

surfers--mostly feral Aussie travelers--to explore most of western Indonesia:

Desert Point on Lombok, Lagundi Bay on Nias, the Hinakus and Mentawais

off Sumatra. Each new discovery the variation of a theme that marked the

era: perfection found, perfection revealed, perfection joined, perfection

lost.

Consider the great Indonesian wave

rush. Touristing French and Australian surfers had been riding the beach

breaks of Kuta, on Bali, since the early 1970s; a young Bertie Barkson

and his mates rode the peeling lefts of Kuta Reef off the end of the airport

runway. But then in 1971, while on Bali filming The Morning of the Earth,

Australian filmmaker Alby Falzon took surfers Rusty Miller and Stephen

Cooney on a day trip out to the temple at Uluwatu, on the southwestern

tip of the island. Falzon's tale is one of the greats: seeing the lines

of swell sweep the cliffs, tramping through the countryside, looking for

a way down to the water, the heat, the curious villagers, the ravine,

the cave, and through the cave a path to the reef and one of the best

waves the surfing world had ever seen. Uluwatu's discovery rocked the

surf world. Gerry Lopez, the most famous surfer at the time, flew over

and set to colonizing the Bukit peninsula one glassy barrel at a time.

But Indo-Inflation was already setting in. American surfers Bob Laverty,

Bill Boyum and Bert Barkson, in an attempt to one-up the Ulu converts, blazed

a trail through the untracked jungles of nearby Java and a wave they'd

spied from an airliner in a region called Grajagan. Within a year, G-Land

was the spot: better, longer, faster--more perfect--than Uluwatu and a

lot less crowded. This insatiable drive would, within the decade, bring

surfers--mostly feral Aussie travelers--to explore most of western Indonesia:

Desert Point on Lombok, Lagundi Bay on Nias, the Hinakus and Mentawais

off Sumatra. Each new discovery the variation of a theme that marked the

era: perfection found, perfection revealed, perfection joined, perfection

lost.

This pattern spread far beyond Indonesia. When in 1972 two young Southern California surfers, Craig Peterson and Kevin Naughton, embarked on what would turn out to be a three-year on-again, off-again odyssey throughout Central America and Africa, the articles the duo produced for SURFER Magazine became instant classics--still the high-water mark of the surf-travel genre, some 27 years later. But while their playful custom of "drawing no maps, naming no names" seemed in sync with their expeditions through Northern and West Africa, the custom had more ominous origins in their series of Central American journeys. Here, in El Salvador and later in Mainland Mexico, Naughton and Peterson found the perfection we all were searching for. But they also found colonies of fellow travelers who'd got there first and now sought to zealously protect "their" nirvana from other well-meaning pilgrims. Particularly volatile were a group of Laguna Beach surfers in Petacalco, Mexico, a secret society of the beach break, sworn to secrecy, committed to intimidation and even threats of violence to protect water rights.

The

discovery of a dreamy right on Nias inspired surfers to look

beyond the perfect lefts of Uluwatu and G-Land. Photo: Kin.

The SURFER articles ran, the nether-regions

loosely placed on the map. But a new mood was established among both traveling

surfers and the media that once openly celebrated the spirit of discovery.

This was wrought to the point of absurdity with a two-part 1974 SURFER

series in which Hawaiian Randy Rarick, the new Peter Troy, led an overland

surfari up the unexplored coast of Angola in Southern Africa. Rarick,

along with photographer Peter French and Brian Hinde, uncovered a half-dozen

good surf spots, scoring excellent waves where no surfer had been before.

The ensuing magazine features, however, which just a few years previous

would have revealed this new bounty with a sense of pride, included not

a single surf shot nor any of the premium breaks the team found. "To

encourage surfers to use their imagination," an editor later told

Rarick. The message was clear: perfection was something to be kept hidden,

not shared.

The SURFER articles ran, the nether-regions

loosely placed on the map. But a new mood was established among both traveling

surfers and the media that once openly celebrated the spirit of discovery.

This was wrought to the point of absurdity with a two-part 1974 SURFER

series in which Hawaiian Randy Rarick, the new Peter Troy, led an overland

surfari up the unexplored coast of Angola in Southern Africa. Rarick,

along with photographer Peter French and Brian Hinde, uncovered a half-dozen

good surf spots, scoring excellent waves where no surfer had been before.

The ensuing magazine features, however, which just a few years previous

would have revealed this new bounty with a sense of pride, included not

a single surf shot nor any of the premium breaks the team found. "To

encourage surfers to use their imagination," an editor later told

Rarick. The message was clear: perfection was something to be kept hidden,

not shared.

Cory

Lopez' lesson in modern French surfing. Photo: Sylvain Cazenave.

The

'70s did provide a highpoint in the travel ethic. In 1974, Larry and Roger

Yates' fine documentary Forgotten Island of Santosha took the myth of

perfection and portrayed it in a spiritual light that transcended its

blatant use of the pseudonym--Santosha, ironically enough, being in reality

Tamarin Bay on Mauritius, where De Rosnay reported his "wonderfully

shaped waves" more than a decade earlier.

The

'70s did provide a highpoint in the travel ethic. In 1974, Larry and Roger

Yates' fine documentary Forgotten Island of Santosha took the myth of

perfection and portrayed it in a spiritual light that transcended its

blatant use of the pseudonym--Santosha, ironically enough, being in reality

Tamarin Bay on Mauritius, where De Rosnay reported his "wonderfully

shaped waves" more than a decade earlier.

"The Forgotten Island of Santosha is more than just an island," narrated Yates. "It is many islands, and it is this island Earth on which we live. It is a state of mind...and of being...and a land of forgotten dreams. An island bound by the spirit of the sea and living within the spirit of man."

If it seems like New Age rambling today, consider this: In 1974, Tony Hinde, a young goofyfoot from Sydney, saw Santosha and discovered its spirit in his soul. The vision of perfection sparked a journey to South Africa via Southeast Asia, where Tony eventually found himself in Goa, India, signing aboard a yacht bound for Durban piloted by an eye-patched pirate with a monkey on his shoulder. Turned out, the pirate was a lubber in disguise--the cruise turned bad, then worse until finally, in the blackness of an Indian Ocean night, the schooner ran itself up onto the dry coral of an atoll. Here a shipwrecked Hinde stayed for a season, building a native dhoni in which to sail down the island chain to some sort of civilization. But on the way, he passed several reefs that warranted checking in an offshore wind. When the monsoon switched, Hinde sailed back up the archipelago, tacked around the corner of one of the more promising reefs and...he had found his Santosha.

"I took one look at the waves, the island, the clouds," recalls Hinde, today known as Tony Hussein, "and said to myself, 'My road stops here.'" And so surfing had come to the Maldives.

That same year, on another shore, Aussie wanderers Kevin Lovett and John Geisel struck up a friendship with another ferry passenger, sailing along with them from Padang, Sumatra, to an offshore island. Lovett, too, had been seduced by Yates and his Santosha manifesto, this time as seen in the SURFER review of the film.

"The overwhelming sense of adventure, the allure of the unknown, the ecstasy of riding perfect, uncrowded waves," wrote Lovett, some 23 years later in The Surfer's Journal, "these feelings were to crystallize...into a thought that became the nucleus of our dream. The Surfer's Dream."

The new travel mate was Peter Troy. The island: Nias. The discovery: the dream right at Lagundi Bay. Lovett had found his Santosha, an Indian dialect's word for "peace."

That peace would become much harder--and more expensive to come by--in the years to come.

Fleeing Ourselves

Kelly

Slater in the Mentawais: the new millennium's ultimate

surfer on the ultimate surf trip. Photo: Grambeau.

Surfers

were everywhere by the beginning of the 1980s--throw a dart at just about

any coast, and chances are some board-toting brigade had checked it out

on every tide. There were still a few fertile crescents: Costa Rica was

still uncharted, the India's Andaman Islands, the Philippines; Tony Hussein

still hadn't been able to convince any of his mates to come visit the

Maldives. Tahiti, the birthplace of modern surfing, was only now revealing

some of her richest jewels: Hapiti on Moorea and Huahine's passes. But

something was happening in the South Pacific that would change surf travel

forever. A California surfer named Dave Clark was setting up a very novel

experiment on an island called Tavarua, a pinprick of white sand and green

palms with two of the best waves ever found fringing along its reefs.

And who better to introduce the concept of the surf resort to the surfing

world than Kevin Naughton and Craig Peterson, the still-restless '70s

icons of the open road? The story broke in the December 1984 issue of

SURFER, a Peterson classic on the cover: Naughton, poised to jump out

of an anchored boat, a perfect, peeling left in the background. It looked

like Santosha, but this was a modern dream, tailor-made for a new wave

of dreamers. In a single passage, Naughton the adventurer summed up a

growing motivational force that would do much to change the shape of surf

travel in the next 15 years.

Surfers

were everywhere by the beginning of the 1980s--throw a dart at just about

any coast, and chances are some board-toting brigade had checked it out

on every tide. There were still a few fertile crescents: Costa Rica was

still uncharted, the India's Andaman Islands, the Philippines; Tony Hussein

still hadn't been able to convince any of his mates to come visit the

Maldives. Tahiti, the birthplace of modern surfing, was only now revealing

some of her richest jewels: Hapiti on Moorea and Huahine's passes. But

something was happening in the South Pacific that would change surf travel

forever. A California surfer named Dave Clark was setting up a very novel

experiment on an island called Tavarua, a pinprick of white sand and green

palms with two of the best waves ever found fringing along its reefs.

And who better to introduce the concept of the surf resort to the surfing

world than Kevin Naughton and Craig Peterson, the still-restless '70s

icons of the open road? The story broke in the December 1984 issue of

SURFER, a Peterson classic on the cover: Naughton, poised to jump out

of an anchored boat, a perfect, peeling left in the background. It looked

like Santosha, but this was a modern dream, tailor-made for a new wave

of dreamers. In a single passage, Naughton the adventurer summed up a

growing motivational force that would do much to change the shape of surf

travel in the next 15 years.

"Throughout the '70s, Craig and I could probably be found only by search party. We forged our way through the jungles and deserts of Africa, Central America, South America, lived like gypsies in Europe, and hopped cargo flights and mail boats to esoteric islands. What we usually discovered were the places not to go for good waves. In the '80s, it's our creditors who are organizing the search parties...we'd long ago shelved all travel exploration plans."

The new gospel all the more potent having been sanctified by St. Naughton and the Holy Peterson.

There had been surf camps. By 1978, the Boyum Brothers, Bill and Mike, had introduced the surfing world to the idea with their jungle camp at G-Land in Java, and with it the pay-to-play concept. But Clark and Funk's Tavarua was something different. In the mid-1980s, a trip to Grajagan was still an adventure; the boat ride through the treacherous reef pass still is. This new sort of resort in Fiji, however, was accessible adventure, provided to any surfer with a travel agent and a credit card. Pre-packaged perfection, the Surfer's Dream realized, but with three gourmet meals a day and a hibiscus blossom on your pillow.

Today,

Tavarua Island is still the gold standard of surf resorts, despite the

worldwide proliferation of camps, resorts and tours. In the United States

and Australia, at least a dozen travel companies specialize in surf travel,

offering destinations like Samoa, Tahiti, the Philippines, New Guinea,

Indonesia, the Maldives--everything from rustic bungalows in Tonga to

the ubiquitous luxury yacht trips through Sumatra's Mentawais.

Today,

Tavarua Island is still the gold standard of surf resorts, despite the

worldwide proliferation of camps, resorts and tours. In the United States

and Australia, at least a dozen travel companies specialize in surf travel,

offering destinations like Samoa, Tahiti, the Philippines, New Guinea,

Indonesia, the Maldives--everything from rustic bungalows in Tonga to

the ubiquitous luxury yacht trips through Sumatra's Mentawais.

Meanwhile, most of the regions pioneered in the early days have long established surfing communities of their own: England, France, Spain, Portugal, Brazil, Japan, Tahiti, Bali, South Africa; Mexican locals dominate the peak at Puerto Escondido, and Puerto Rican surfers win contests at Pipeline. In the last decade of the 20th century, the surfer's world seemed to shrink more than in the previous nine.

And still the spirit survives. Photographer John Callahan, armed with Admiralty charts and fought-for Indian government permits, sails through the Andaman Islands in the Bay of Bengal, looking for a right point. Dr. Mark Renneker, a surfing throwback to the scholar/explorer of old, charters voyages to the Poles--or at least as close as he can come and still find a fluid medium--breaking waves in Iceland and Antarctica. And recently, two young Southern California surfers, Shayne McIntyre and Jon McClure, surfed their way through Russia's Kuril Islands; next stop, the coast of Oman, chasing a tale they'd heard from a U.S. Marine of desert tubes and offshore winds in the Arabian Sea. It is the year 2000--they have their boards, their backpacks and their dreams.

So go back and look at the photo that leads off this feature. Photographer Bernie Baker, 19 years old, sitting on the highway guardrail above Zunzal in El Salvador in 1970, a full 30 years ago. His 6' 11" Joe Blair ski balanced carefully on his lap; Bernie's pack a whole lot emptier than when he boarded the Greyhound bus next to Foster's Freeze in Carpenteria some five months previous. Arms and legs drawn in, head down, pensive, wondering, perhaps, what strange compulsion led him to this spot so far from home--so far from anything he knows. Not realizing, at the moment this photo was taken, that the answer lies right in front of him, peeling toward shore with majestic symmetry.

Like all the surfers who've gone before him, and all of those who've gone since, Bernie is looking for waves. For fun.